HISTORIC ESSEX – the blunder that led to Essex's County regiment being lost in Afghanistan

By The Editor 7th Sep 2021

The current Royal Anglian Regiment has been deployed to Afghanistan several times, in 2007, 2009 and 2012. But its history in that troubled country goes back much further if we look at its parent regiments which were merged through the years to form the present unit.

The Essex Regiment has a particularly tragic connection with Afghanistan, dating back to its days as the 44th or East Essex Regiment – all because of the blunders of a sick and aged commander who should have been kept at home.

Afghanistan's closeness to the North-West Frontier of India always made it of interest to the British, but they avoided direct war until 1838-1842 when they invaded and deposed an Amir, Dost Mohammed, who was getting too friendly with Britain's rival, Russia.

They installed a puppet ruler, Shah Shuja, and moved a garrison into Kabul in 1841, including the 44th Foot and several thousand Indian troops. They were commanded by Elphey Bey, an officer whose career went back to Waterloo and who was suffering from chronic bouts of fever and rheumatic gout.

Instead of occupying a nearby strong fortress, he insisted that the troops and their families be accommodated in an encampment with a low-lying rampart and shallow ditch, too large to properly guard, and dominated by nearby heights.

Predictably the local tribesmen began to rebel in favour of the ousted Dost Mohammed, and the garrison's position became more and more threatened. In November the British Political Officer was hacked to death in the town, and Bey's indecisive response led to a full-scale siege, with 4,500 troops and 12,000 camp followers penned up in the camp.

Complicated negotiations followed, and ignoring the advice of his junior officers who urged strong action, Bey agreed to evacuate Kabul, escorted by Afghan tribesmen. They set off on 6 January 1842 on a journey which involved an 80-mile trek through snow-filled passes guarded by tribesmen over whom Dost Mohammed had little control.

Hounded from the first, the column only managed six miles on the first day and lost numerous stragglers, much of their baggage and most of their tents. Many more died of exposure overnight.

The next day was even worse, with just four miles covered, and temperatures plunging to -10 degrees overnight. The third day the East Essex Regiment cleared the entrance to a pass with their bayonets, but as the column entered the five-mile pass hemmed in by sheer cliffs, snipers opened fire and there was a panic. 3,000 were left dead.

By the fifth day just 450 troops and 3,000 civilians were left. The thirty British wives and children were taken into the protection of an Afghan chief. Most of the Indian troops were dead or dying as they were inadequately clothed.

The survivors struggled through to the village of Judgulluk, where Bey attempted more negotiations – only to be kidnapped. Finding another pass blocked by a huge barrier of prickly holly-oak, a terrific struggle ensued with just eighty making it through.

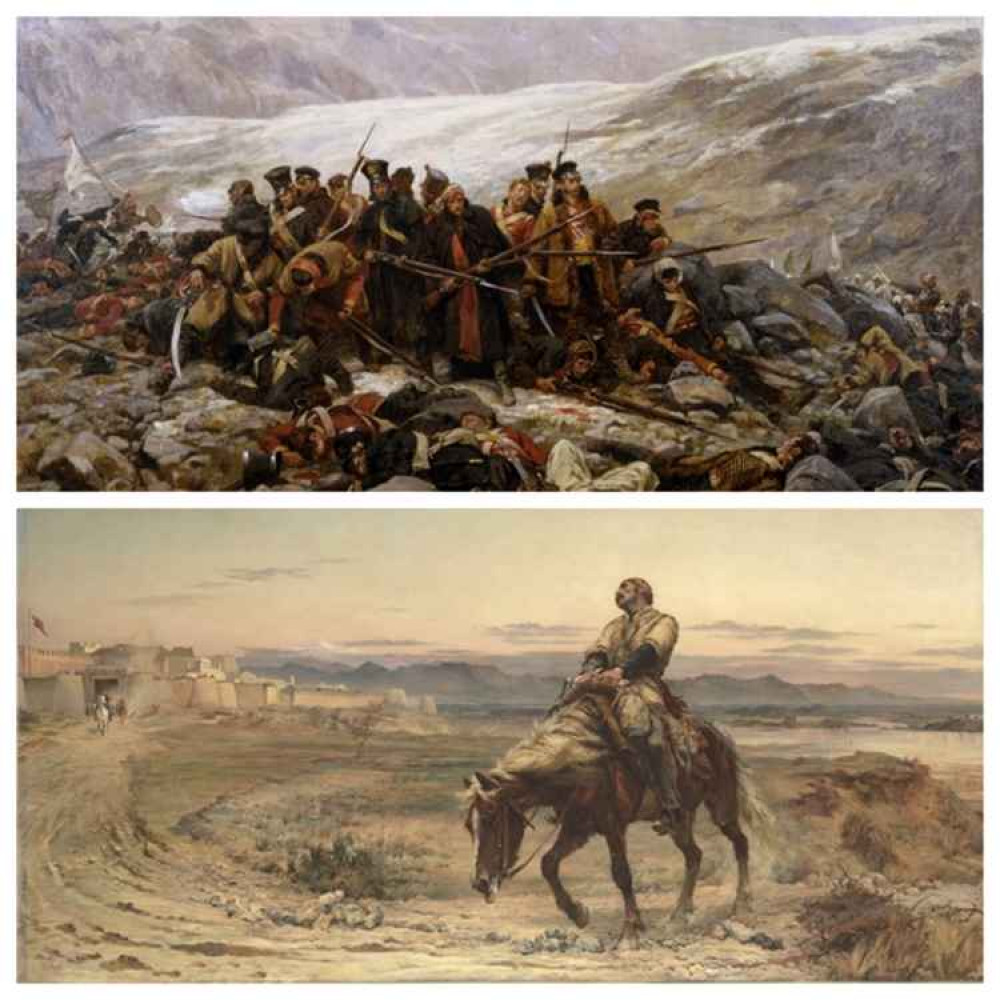

On 13 January the tattered remnants of the 44th made their last stand at Gandamak, an event commemorated in a famous painting by William Barnes Wollen, kept at the Essex Regiment Museum in Chelmsford. Refusing to surrender, they finally ran out of ammunition and were overwhelmed. Just six were taken prisoner, including Lieutenant Souter who had wrapped the regimental colours round his body to save them.

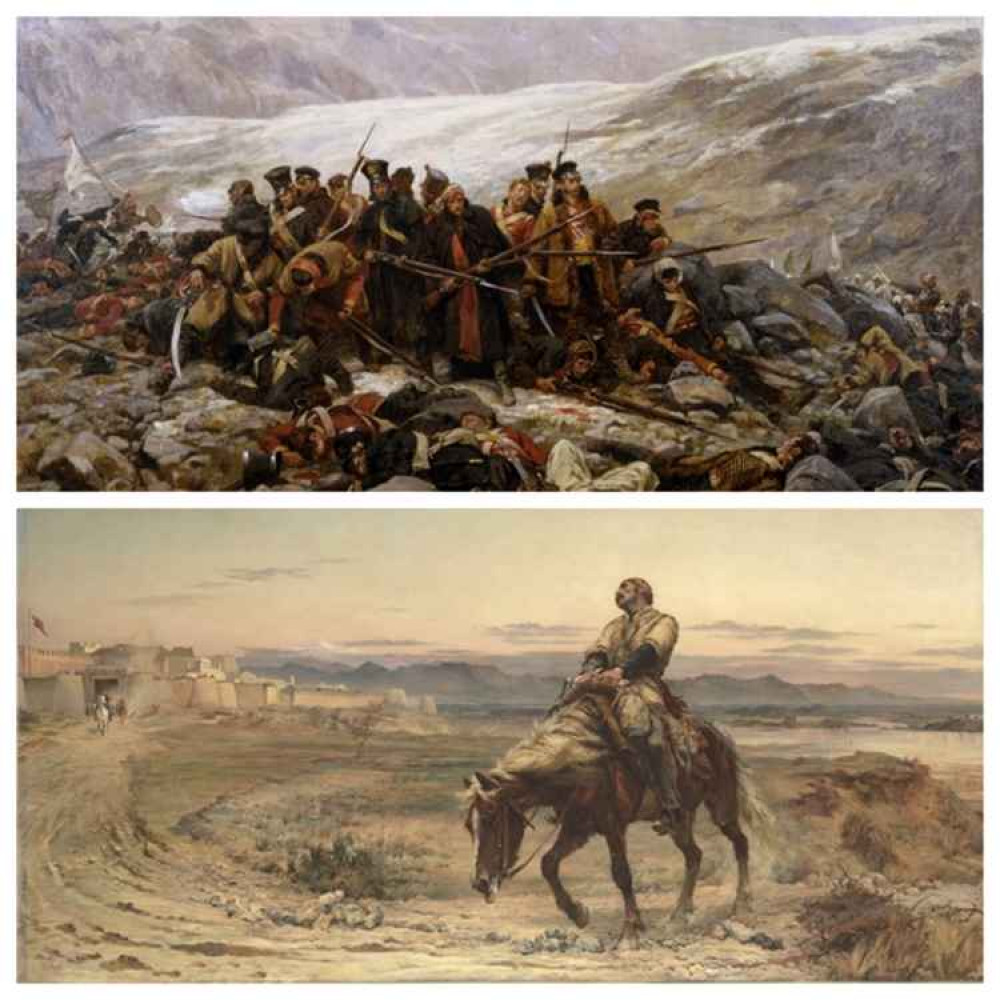

Apart from these and other prisoners who were returned (including the British wives and children), just one man made it to safety – military surgeon Dr Brydon, who had ridden on with a dozen other mounted men and was the only one to make it to Jalalabad, the nearest British base.

Though nearly 180 years distant, a visit to the Regiment's museum in Chelmsford makes this story very fresh, especially as we reflect on the continued complexity of our dealings with Afghanistan.

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

maldon vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: maldon jobs

Share: